If Colonial Newport was known as one of America’s most active slave ports, it was equally known as one of the new country’s most liberal communities in the pursuit of religious freedom. As Quakers, Baptists, and Jews all came to the colony’s shores in search of religious toleration and expression; these same persecuted minority religious groups were actively involved in trading and owning African slaves. These slave trading and owning families would also convey their religious beliefs onto their slaves by encouraging them to assimilate into the religion of the household. As Africans lived, worked, and worshiped together with their masters, many would eventually achieve freedom either by manumission or through work and self-purchase. Click here to view a list of free African Head of Households in the 1774 census

“Negro man and woman, in 1735, by Ind’y & Frugality, scraped together 200 or 300 (English) pounds. They sailed from Newport to their own country, Guinea, where their savings gave them an independent fortune.”

– Rhode Island Historical Society Publication, 1894

Despite the rigors and restrictions of enslavement, Africans would find time to assemble for both religious and family purposes. A general Newport custom was to permit slaves to have personal and family time on most Sundays. This was a time for both enslaved and free Africans to come together for family and recreational activities.

Despite the rigors and restrictions of enslavement, Africans would find time to assemble for both religious and family purposes. A general Newport custom was to permit slaves to have personal and family time on most Sundays. This was a time for both enslaved and free Africans to come together for family and recreational activities.

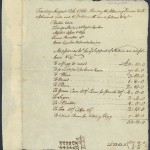

African Caesar Lyndon, a slave of Rhode Island Governor Josias Lyndon, writes in his personal diary of a country picnic. Dated Tuesday, August 12, 1766, he tells of going to Lawton Valley in neighboring Portsmouth with Sarah Searing and several other enslaved and free Africans, including Boston Vose, Zingo Stevens & Phillis Lyndon, Neptune Sisson & wife, and Prince Thurston. The diary includes a detailed list of necessaries for ye support of nature including:

- A Pig To Roast

- Paid For House Room

- Wine

- Bread

- Rum

- Green Corn

- Limes For Punch

- Sugar

- Butter

- Tea & Coffee

- 1 Pint Rum (for butcher) for Killing Pig

Beginning in Boston in 1765 and spreading to other Colonial communities,”Liberty Trees” were being planted and small commons were established as symbolic rallying points for the growing resistance to the rule of Great Britain over the American Colonies. In Newport, the Liberty Tree was located at the corner of Thames and Farewell Streets, directly across the street from the home of William Ellery, future signer of the Declaration of Independence.

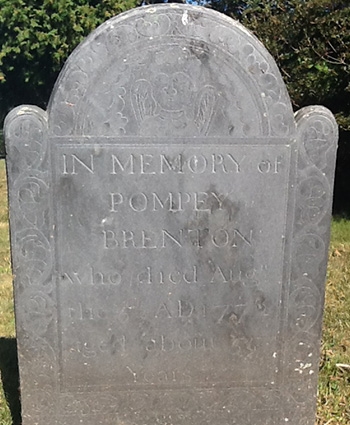

Negro Governor Pompey Brenton

Ironically, beginning each spring as early as 1756, enslaved and free Africans would assemble at the public commons (the future site of the Liberty Tree) to hold elaborate multiple day ceremonies, where they would vote for and elect an African Governor. The election was held in June of each year and any African who owned a pig was eligible to vote. These highly festive ceremonies were a combination of African and European traditions. After the election votes were tallied, the new African Governor would be honored in an inaugural parade accompanied with food, games, socializing, and dancing in a celebration of the entire African community. The cultural and religious importance of Newport’s annual election of an African Governor cannot be underestimated. These ceremonies reflect an important re-connection to Africa. It is possible that the site was specifically selected because of its strategic location in close proximity to the African community burying grounds and where one of the largest trees (a Buttonwood) at the time stood. West African religion then and today recognizes the important interrelationship with nature and man. These ceremonies also had strong resonances of West African religious customs. Pompey Brenton, a free African who died in 1772 and is buried in God’s Little Acre was elected as one of many of Newport’s African Governors. The tradition of Negro Elections is later seen in Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

The complexities of Africans living together in a community where some are free and others are enslaved required “creative survival” practices to enable them to carry on any semblance of a meaningful life. One of the most challenging societal circumstances for Africans in Colonial Newport was the ability to marry and maintain a family life under the considerable constraints of the dominant slave system. Many enslaved and free Africans would form common-law relationships while others, with the permission of their masters, would marry officially through their house of worship. Freeman Cudjo Vernon and enslaved Sylvia Gould would marry on November 18, 1783 in the 1st Congregational Church, but not before requesting permission the year before:

To Mr. Samuel Vernon

Newport, 11th November, 1782

Honored Sir: This is to ask your consent, and all concerned, whether your humble servant may be married to a black woman called and known by the name of Sylvia, as soon conveniently may be; if you should judge needful, pray acquaint my old master, Mr. William Vernon, with my intention, in order to obtain his consent. I doubt not but you will do everything necessary, and beg leave to subscribe myself.

Your Obedient Servant,

The mark X of Cudjo Vernon

– Newport Historical Magazine, April, 1884

1781 watercolor of a member of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment

A pivotal historical moment and opportunity for Africans slave and free comes in August of 1778 when the 1st Rhode Island Regiment sees action in the Battle of Rhode Island. Earlier that year, the Rhode Island General Assembly enacted the following:

“It is voted and resolved that every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave in this state may enlist to enter either of the said two battalions to serve during the continuance of the war with Great Britain.”

The regiment, comprised of mostly enslaved and free African, Indian, and Mulatto men take the field for the first time as an organized fighting force in defense of the colony and fledgling nation. Their gallantry in that and following battles would provide the impetus for some individuals to recognize that men willing to fight and possibly die for a new country that did not accept them as equal was incongruous to the ideals of American liberty and freedom.

“If you say you have the right to enslave (Negroes) because it is for your interest, why do you dispute the legality of Great Britain’s enslaving you?”

– A True Son of Liberty,

Newport Mercury, January 8, 1768

By 1784, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed the Negro Emancipation Act, decreeing that all children of slaves born after March 1, 1784 remain as slaves as children, but would be free after attaining the age of twenty-one for boys and eighteen for girls. All slaves born before 1784 would remain slaves for life. In the 1790 federal census there were still over 260 slaves in Newport households. African families in the same census year also boasted a sizable free community, many being former slaves within the Colonial seaport. Click here to view a list of free Africans in the 1790 census

By the end of the 18th century nearly all Africans were free in Newport, but free life was still subject to the former masters’ standards of conduct and living as clearly exemplified in the December 5, 1807 Obituary of Cato Stevens in the Newport Mercury newspaper:

“Died, yesterday morning, after a short illness, Cato Stevens, a faithful servant and an honest man; — though black in colour, his actions were truly white; — having lived near fourteen years in the service where he died, with honour to himself, and satisfaction to his employer. — His relations and friends are invited to his funeral, at the house of Mr. Elam, in Newport, to-morrow at one o’clock. The corpse to move at two precisely.”

One of the more interesting aspects of free life for Africans in Newport is their living patterns. Newport is one of the very few early American communities that did not restrict free Africans on where they could live. While many early communities would confine Africans to living in the poorest and least desirable sections of town with racially distinguishable names such as Little Liberia, Little Africa, New Goree, and Snow Town, free Africans in Newport, like their white counterparts, lived in proximity to either their trade and/or their place of worship. As an example, Africans who were furniture makers, silversmiths, and other skilled trades mostly lived in the (Easton’s) Point Neighborhood of Newport within the largely Quaker artisan community. One section of Newport that became a significant area where free Africans would not only live but purchase and own their homes is an area between Spring and Thames Street that between 1790 and 1820 was commonly called “Negro Lane” or as Pope Street today. Free men of color including Occramar Marycoo, Salamar Nubia, Baccacus Overing, Lincoln Elliot, and Peter Armstrong were Pope Street homeowners.

Here are a few extant homes in Newport: