“Hear the words of the Lord, O ye African race; hear the words of Promise. But it is not meet to take the children’s bread and cast it to the dogs. Truth, Lord, yet the dogs eat of the crumbs that fall from their master’s table. O, African, trust in the Lord: Amen. Hallelujah, Praise the Lord, Praise ye the Lord. Hallelujah. Amen.”

– The Promise Anthem, Newport Gardner

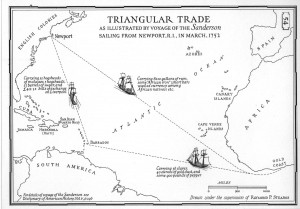

Only a small fraction of the enslaved Africans brought to the New World over a 300 year period ended up in North America, with the vast majority of slaves shipped to the West Indies and South America. The first African “forced immigrants” arrived in Rhode Island sometime around 1652, and the first documented slave ship, the “Sea Flower” arrived in Newport in 1696.The earliest documented slave manumission in Newport was recorded in 1673.

“…thirtith day of March John Champlin heire to

John Card Deceased did declare that he gave his Negro

Salmerdore his Freedom forever Newport on Rhode Island.”– Rhode Island Land Evidence Records

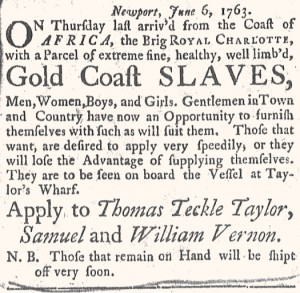

As early as 1708 enslaved Africans outnumbered white indentured servants in Newport ten to one. Between 1705 and 1805, Rhode Island merchants sponsored at least 1,000 slaving voyages to West Africa and carried over 100,000 slaves back to America and the West Indies. (Click here for a list of the names of Sloop and Brig slavers) Many enslaved Africans would originate from what is today Ghana, and others would hail from Sierra Leone, Senegal and Guinea. Rhode Island as an English Colony would deal almost exclusively with and through British slave forts along the West African Gold, Ivory and Grain Coasts. The infamous Anomabo, Cape Coast and Elmira Slave Castles of what is present day Ghana would be the last African soil captives would touch before being shipped to the New World.

The Colonial Town of Newport played a leading role during the European Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. By 1755, several thousand Africans lived, worked and eventually died in this New England seaport. At the peak of what historians commonly call the “Golden Age” Africans comprised nearly 20% of the total town population with one in three Newport families owning at least one slave.

In 1774 there were two dozen rum distilleries active on Newport’s waterfront, producing much of the world market’s “Guinea Rum.” From the West Indian Islands including Barbados, Antiqua and Jamaica came to Newport the raw materials needed to make the rum; molasses from refined sugar harvested by and through African slave labor. Several Rhode Island merchants not only distilled and sold rum, but also had financial interests in large sugar plantations in the West Indies. Men like Abraham Redwood of Newport, who inherited from his father a large sugar plantation in Antigua that consisted of over 200 slaves. Redwood would use the profits from his inheritance, slaves and other trading activities to underwrite the founding of Redwood Library in Newport, America’s oldest extant library.

“The Sugar they raised was excellent; nobody tasted blood in it.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

Newport Mercury June 20th 1763

The European Slave Trade was such a lucrative market that it touched nearly all aspects of the maritime economy and its merchant participants. Indeed, the European Slave Trade could be termed the world’s first and most extensive “Equal Opportunity Employer” with all religious groups actively participating in the African trade. During this period we find Quakers, Anglicans, Baptists, and Jews in Rhode Island all occupied within the trade. Nearly all of Newport’s leading and founding families were involved, most notably Champlin, Lopez, Redwood, Buckmaster, Brenton, Vernon, Wanton, and Malbone. By the mid-18th century, Rhode Island’s success in the trade and ownership of slaves gave direct rise to one of America’s first business cartels. The United Spermaceti Candle Making Company was founded in Newport and its founding partners including the Brown brothers of Providence, Aaron Lopez, and Jacob Rodriguez Rivera of Newport. The company controlled the American market in the production and distribution of spermaceti candles. The candle factories were located in both Providence and Newport and the labor force included many slaves. Ironically, the founding partners would later become most famous for being the early contributors to Brown University in Providence and Touro Synagogue in Newport, the oldest existing synagogue in North America.

Simeon Potter Overmantle

– Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society

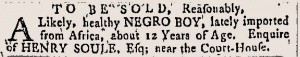

What sets New England apart from the conventional understanding of the American Slave Trade is that many Africans who would arrive, particularly in Newport, were young, many times children. Unlike the vast sugar, coffee, tobacco, and cotton plantations of the West Indies and the American South, many Rhode Island plantations were largely horse and livestock farms with severe limitations in weather and soil conditions needed to sustain any significant cash crop-based economy. While a number of slaves toiled in the Rhode Island plantations in Narragansett County, many more would become the skilled artisans and labor force in the urbanized seaport towns of Newport, Providence, and Bristol. Historical records of the time reveal a Newport maritime trade economy that was largely dependent upon the skilled work of Negro, Indian, and Mulatto servants (slaves). By bringing an African child to Rhode Island, the Master had five to six years to apprentice that child to become a skilled worker in one of many trades including rope making, barrel making, stonemasons, carpenters, furniture makers, shipbuilding, rum making, candle making, and silversmiths.

Newport Mercury April 21, 1766

Newport was an important center for the chocolate industry in early America, and Newport’s Jewish merchants played a leading role in producing and trading chocolate throughout the world market. In 1769, several Newport slaves are listed as Chocolate Grinders; one, in particular, Prince Updike, is listed as a Master Chocolate Grinder, grinding several thousand pounds of sugar and cocoa into chocolate for shipment to the European markets. Updike dies in 1781 and is buried in God’s Little Acre.

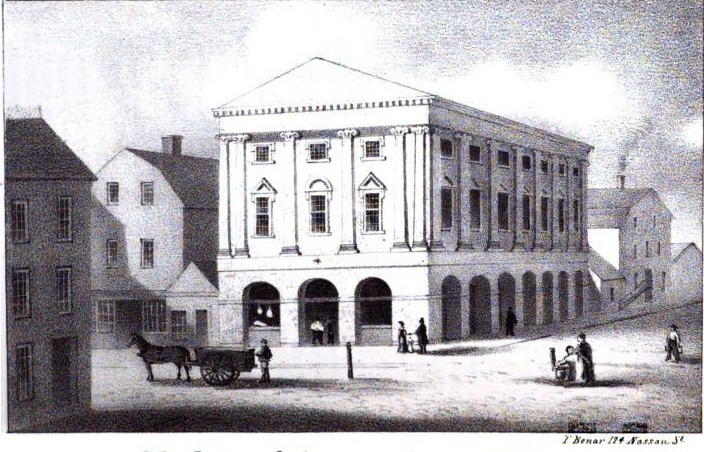

These skilled trade priorities that required levels of education and craft training within the slave economy in Newport would create a distinct difference between slavery in Colonial Newport as compared to the American South and West Indies. Several of America’s most historically significant Colonial structures still standing today were constructed by highly skilled artisan labor that included both free and enslaved Africans. In Newport, these existing historic buildings include Touro Synagogue, Redwood Library, Brick Market, and the Old Colony House. The John Brown House in Providence includes at least two builders listed as Negros.